Remembering the Doughboys of Cascade County

On November 11, 1918 the Great War came to an end. This world consuming event did not tear up our fields and homes in Montana, but it forever scarred the Montanans who fought across the ocean. The war came home in their memories, their personalities, and in their very being. The war changed the people that served overseas, and it changed the families and communities in Cascade County.

The exhibition Remembering the Doughboys of Cascade County was on display at The History Museum November 2018 to July 2020. This online presentation was published November 2020 with expanded material.

Excerpt from the History and Roster Cascade County Soldiers and Sailors 1919:

To write a complete history of the part played by Cascade County men in the Great war would be a compilation of data and statistics which would cover every branch of service in all of their separate engagements, for scarcely a unit of the army, navy or marines, or a skirmish on any of the widely scattered fronts but that Cascade County men were engaged. Likewise, to truly portray such a story one needs must be gifted an immortal pen, for truly those words as fall to common usage but illy depict such a struggle. Our language is strangely lacking when it comes to expressing real, human emotion.

From an historian’s point of view it is unfortunate that Cascade County men could not have gone to the front as a unit, for then their history could be far more complete; but while the story of their exploits may be traced on printed page, the history of their deeds was written by the points of their bayonets and by their blood on many foreign fields. And as these boys of ours fought for accomplishment rather than for glory, for democracy rather than for self-exploitation, for America rather than for themselves, it is well that they served their country wherever she chose to place them.

The American Field Service

The American Field Service (AFS) was an organization of volunteer American ambulance drivers and transport truck corps who aided the French Army During World War I. The AFS, first organized in 1914, grew over the next 3 years to reach almost 5,000 volunteers. Truck corps delivered ammo and supplies to the front lines while ambulances transported wounded soldiers back to aid stations. When the United States joined the war, the French requested to keep the use of the AFS. The AFS was absorbed into the American Army and then loaned back to the French as to not disrupt their established operations. They continued supporting the French throughout the war until its end. The Americans who volunteered saw more battles than any that came with the Army later. Five of those men were from Cascade County.

John Berger

John Berger Jr.

John Berger enlisted in the American Field Service in August, 1917. He drove trucks of ammunition from the trains up to the front lines. Berger was the first of the five Great Falls, Montana men to come home, returning about a year after he left. His health deteriorated after he suffered from shell shock and “an attack of diabetes”. Berger was sent to New York before returning to Cascade County. He was said to be one of the first 25 people treated with insulin. He was later known as the oldest living diabetic as well. He saw many German prisoners in his section and brought home a collection of war souvenirs purchased from German soldiers.

John Berger printed in History and Roster: Cascade County Soldiers and Sailors, 1919

Irving Colgrove Cooper

Irving Cooper departed for service November 19, 1917. He served in France until April, 1918 when he was sent to Italy for 6 months. He returned to France after and enlisted with the US Army as an engineer. He saw heavy fighting in the Argonne Forest. He returned to the states in March, 1919 and stayed in a hospital in New Jersey for a month and half. He was treated for shell shock and influenza before he was released. The war did not end for Cooper. In 1927, he was put in a veteran’s hospital and remained there until his death 44 years later.

Irving Cooper

Henry Hamilton

Henry Montgomery Hamilton

After graduating from Dartmouth University in 1917, Henry Hamilton was recruited by the American Field Service (AFS.) Hamiton’s degree in French made him a valuable recruit.

Hamilton’s Ambulance unit was attached to a French division. When the French division moved to the front, the ambulances went with it. the Germans shelled the roads heavily during the day, which required the ambulances to run at night. Wounded men had to be driven 15 miles back to an aid station.

After the American Army absorbed the AFS, Hamilton worked in Italy for the Red Cross. Hamilton later enlisted with the French Army, but by the time he had finished artillery school and got to the front again, the war was over.

Hamilton led the 1920 Great Falls Armistice Day Parade in his French uniform. When he got home, western artist Charlie Russell was on the phone, wanting to paint Hamilton in his uniform. Hamilton kindly declined; he had enough of the war.

Left: Henry Hamilton American Field Service (AFS) Uniform, private collection of Mark R. McCaffrey

American Field Service Uniforms were purchased by the recruit upon their arrival in France. The uniforms did not have a strict design standard and had a few evolutions in style. Hamilton’s uniform follows the French military style, which features “ball style” buttons and a single notch collar.

Right: Henry Hamilton’s AFS Medal [2001.096.23]

The red “flaming bomb” insignia was the symbol commonly associated with the AFS. The “A” of the insignia represents “automobile.” The AFS service medal was a mark of distinction for recruits who volunteered before America entered the war and absorbed the AFS. The eagle (left) symbolizes America and the rooster (right) symbolizes France.

Left: Henry Hamilton at Verdun, 1917 in his AFS uniform, Right: Henry Hamilton in French Army Uniform

Scrapbook page from Henry Hamilton Collection [1986.008.0017]

Ira Mose Kaufman

Ira Kaufman, along with Leon Singer and John Berger, went to New York to sign up with the American Field Service, but because their parents were born in Germany, they had trouble getting visas. Kaufman went to Washington D.C. where he had an interview with the French ambassador who approved his service. Kaufman went over with the youthful idea of adventure, but the reality of war put things into perspective. “War is nothing but waste,” he said, “a waste of lives, a waste of property, and a waste of land.” He originally signed up to drive ambulances but ended up driving a supply truck. As he made his trips he felt compassion for the refugees as they fled the fighting, leaving with only what they could carry. “It broke your heart to see them,” he said. When the US Army came, Kaufman was put in charge of a Supply Depot until the war ended. Kaufman got the chance to travel to Paris, Nice, and to other European cities once the war ended.

Ira Kaufman

Left: Group photo, Ira Kaufman far left Right: Ira Kaufman in uniform

Images courtesy of Ike Kaufman

Left: Ira Kaufman’s AFS Medal, Middle: Box made from brass shell with etched AFS horn insignia and “Reserve Mallet,” “1917, 1918, 1919,” Right: Ira Kaufman’s WWI Victory Medal

Private collection of Ike Kaufman

Leon Singer

Leon Frederick Singer

Leon Singer went across the Atlantic with Ira Kaufman and John Berger in the summer of 1917. They all arrived together, but on Singer’s second day in France, he was sent up to a unit just behind the newly established front lines. “We are camped right on the battlefield and trenches are all around us,” he wrote home, “This afternoon several of us took a walk and were in what was formerly the French first line trenches.” After the Armistice, Singer joined Kaufman to travel Italy. After Kaufman left, Singer stayed a few months longer, acting as a French-American interpreter.

The Montana Army National Guard

At the end of 1916, the Second Montana Regiment returned from a successful campaign on the Mexican Border. They had a short rest, but tensions grew in America as Europe tore itself apart. Labor unions within the United States added to the anxiety with their constant threat of strikes. The Zimmerman Telegram pushed the U.S. over the edge in March 1917. On March 25, National Guard units were called up to federal service across the U.S., including the Second Montana Regiment. On April 6, the United Sates officially joined the war.

Over the next week, over 1,500 men reported to Fort Harrison for duty. Their main mission was to protect and guard utility facilities and other crucial points around the state. Company D was sent to Great Falls to protect the dams, utilities, and the Anaconda Copper Mining Company. Now with the U.S. in the War, labor strikes could cripple or even lose the War. During the summer of 1917, two of the most famous events out of Butte caused upheaval: the fire at Speculator Mine and the lynching of Frank Little.

In July, the Guard was told to prepare for overseas service. They were combined with units from Idaho, Oregon, Washington, and Wyoming to become the 82nd Infantry Brigade of the 41st Division. Montana was redesignated form the Second Montana to the 163rd Regiment. They were sent to Camp Green in North Carolina to drill with regular army troops. They transferred to Washington D.C. and then to New Jersey before boarding a ship to England. Unfortunately, this was the last time the Montana battalions were together, as the 41st Division was relegated to replacement and depot status. Around 3,000 soldiers were split up and sent to replace others in various units at the front like the 42nd and 91st Divisions. There were Guardsmen in every major battle the Americans participated. After the Armistice, many troops served in occupation posts in German territory. By March 1919, the 41st Division returned to the United States. By August 1919, all American soldiers had left Europe.

Felt pillow cover from the Mildred Buntrock Estate, circa 1915 made to commemorate the 2nd Montana Infantry with text “U.S. Army on Mexican Border” [CCHS 132-96]

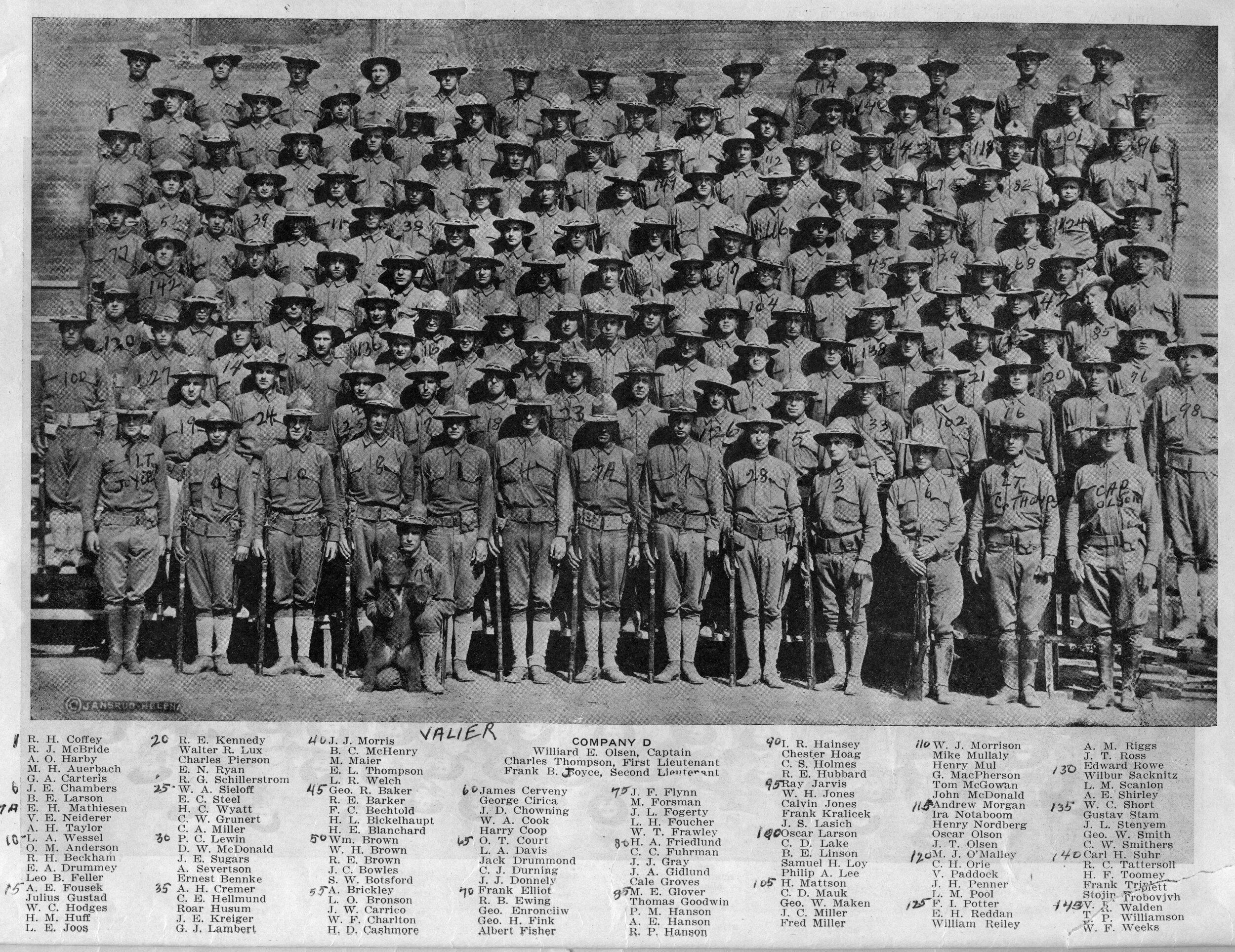

Company D, 1917

Great Falls Tribune January 28, 1918:

Great Falls Boy Writes in France

Tells of Trip on Boat and of the Landing on French Soil for the Big Fight.

Machinist Walter W. Hillstrand of Company M 163rd infantry, American Expeditionary Forces, who was formerly of The Tribune composing room and who enlisted in Company M, Second Montana, last spring, has been heard from in France, hist mother, Mrs. C. A. Hillstrand 2616 First Avenue south, having received two letters from him in one enclosure.

The first was written on board ship on the day of its arrival in port, Monday, December 24, and the second is dated January 2. Both letters were considerably mutilated by the shears of the censor, but what is left of them is reproduced as follows:

“This blooming boat is at last standing still so will take this advantage to write you a few lines. We are just a little way out of the harbor waiting for the tugs to come and pull us in. No doubt you read in the papers the morning before Christmas of our landing safely. We had a very pleasant trip (Scissored). Very few of the boys were seasick. I felt kinder dizzy for a while, but it soon passed over. I did not miss a single meal (deleted). We had our Christmas dinner yesterday, Sunday, December 23. It was a good feed, too, turkey, mashed spuds, corn, gravy, cranberry sauce, asparagus, mince and apple pie, bread, butter, and coffee. I sure got all I wanted. Ate about three pounds of turkey, two cans of corn, big stack of spuds and five pieces of honest-to-God pie. They fed us fine all the way over. (Deleted).

“We had to go to our bunks at 4 in the afternoon and stay there until 8 the next morning. There were no lights from 4 to 8, so we could not see to read or write. We’d just sing, tell stories and one thing another in the dark. We are not allowed to tell what boat we came over on, but you can make a good guess. Do not worry about me. We are just having a nice little tour of the world”

His second letter, dated January 2, reads:

“Just a few lines to let you know I am well, and everything is O.K. We are now somewhere in France. We spent Thanksgiving in New York, Christmas in England and New Years in France and expect to celebrate the Fourth of July in Berlin. It is colder than in England, but we are pretty well fixed to stand the cold. There is no snow here yet. There are men from five different countries in the Y. M. C. A.” (Balance Deleted).

Great Falls Tribune August 11, 1918:

James J. Morris

Mont Prichard, France, June 30, 1918.

Dear Folks:

By the time this letter reaches you, I suppose you will have already learned that our pal Walter Lux has passed away – a complication of Spanish Fever and Pneumonia is responsible. All of his comrades united efforts and made his last rites a beautiful affair. We gathered flowers from the whole country round about (and such flowers as only Franc can produce) until the little chapel was fairly filled. The procession was an imposing military funeral procession – the Montana Band led it. Then with his cassion carriage drawn by four black horses and riders on which was the casket was covered with the American flag and piled about and over with roses of France. Then followed the pall bearers which were Olsen, Anderson, Lambert, Fousek, Steel and myself. And then the whole of the first battalion of the old Montana. After these came the French population nearly “en masse.” A wonderful tribute to the dead American soldier. Walter’s greatest grief will probably be that she was not here in this far off country to have laid him away, but said it was wonderful. Our regret among other great ones was that Walt could not have given his life at the front. We know it should have been Walt’s desire, but it was written otherwise. Walter was a sergeant of our company, was liked by all and he was a soldier from the word “go” and the most conscientious worker I have ever known. Walter’s brother who was in Paris was telegraphed but could not get here in time for the services. Traveling permission is practically impossible at the present time in France, especially at a day’s notice. All of the rest of the boys are in the best of health and pink of condition after a little epidemic which affected almost everyone. I am on guard today walking post because we have had no one but non-coms here until today when we received a couple of hundred per company – alas, the work commences again.

With love,

JIM

Left: Helmet for the 91st Division (Pine Tree Division), originally belonged to Earl C. Wolff. [1991.146.1]

Right: Helmet for the 41st Division, which included the 163rd Infantry Regiment Montana National Guard; helmet originally belonged to Albert Eller. [2018.052.6]

Letters Home: Harold Mady

Great Falls-born Harold Mady boarded a train for Portland on July 25, 1917 along with two friends to join the Marine Corps. He trained at Mare Island, CA, became part of the 5th Regiment of 12th Company, and was sent to France with the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF) in December of 1917. He often wrote home about the local people, the buildings, and his duties. He even wrote letters during his time in the trenches. Many were published in the Great Falls Tribune.

In June 1918 at the Battle of Belleau Wood, Mady was sent to determine the number of machine guns a German unit had. He was shot in the right foot by a sniper but completed his task before making it back to safety. While he was transported to an aid station, Mady was thrown from his stretcher by an exploding shell and suffered several shrapnel wounds. He made it to the hospital without further incident and began his recovery. He chronicled it all through letters to his mother and sisters back in Great Falls. Mady left the hospital in November of 1918. He arrived back in the states two months later. Mady was awarded the Croix de Guerre for bravery in action in a ceremony in Great Falls which was attended by 200 people.

Harold Mady’s helmet, private collection of Mark R. McCaffrey

Harold Mady November 20, 1918 Letter

My Dear Mother and Sisters:

Feel so good about receiving a letter from home will write again today. You know one letter in eight moths should make me ok. I wrote you a letter last night and one today. The first thing I want to know is did you ever receive my insurance policy and my liberty bond? If you didn’t please look into it and get them.

Now that the war is over I suppose we can write a few of our experiences. I was in the front line trenches for five months, three months without ever coming out and believe me it was some experience. I will never forget the first Boche I got. If he was half as scared as I was, I sure pity him. My knees were knocking so bad they sounded like a big drum to me. When we moved into the Belleau Wood and Chateau Thierry, it sure was some sight to see the urban population evacuating the village and either it was continuous stream of old and young moving with only their most prized possessions. Some of the oldest of the population had to be moved by force. They said no we have lived here all our lives let us die here. When we got to the front line, the Germans were breaking the lines. The French told us it was no use to try that the odds were too great but not for us. Our officer said “Stand we will” and then came the Hell. Everything was hand to hand fighting until we turned their faces homeward bound. And believe me they were as sorry looking bunch of Boche when they saw what the “Devil Dogs” could do. It sure is some sight to see your pals rifle go in the air and his nose hit the dirt. Always speak as few words it is “I am His” or else “The ----Boche got me”. In all my time up there, I never saw a one that gave his life that didn’t have a smile on his face. I remember one night a lad from my company received a letter from home telling of the death of his brother. That night he was on a listening post. It must have been the Hand of Fate for he too was amongst the Killed in Action. The last word he said was “Boche” to warn his commander of the attack. We don’t fight the battles over here. Just think of the battle that mother had to fight.

This morning I was wounded I was sent out as observer I got into the German lines OK. But coming back I tried to (unintelligible) machine gun bullet and decided I could not be done. I was not satisfied with that and when I was being carried in, a big G I can (Shell) came over and knocked me off of the stretcher. I sure thought my day had come. The ride back in the “Tin Lizzie” was sure a bad one. I swear I will give all I own to anyone that ever catches me riding in a “Tin Lizzie”. We was taken into a Base [unintelligible] in Paris and then to Base 8 and on to here. You can talk about Paris all you want too, but I know a certain corner in a certain city I would not trade for all of it. I still claim I would rather be a Larry Post in the States than a millionaire over here. The Statue of Liberty will sure have to turn around if it ever wants to see me again once I get home. When we are doing duty, they keep us in what they call billets it is the first time I even heard a cow shed called a billet.

I have so much to tell I cannot set my hand to write. Guess I will have to wait and tell it. But there is one thing sure the next war I am going to have an Army all my own. Ha!

Well Mother keep a stack of “Buck Wheat” cakes and a good cup of coffee on stove because it won’t be long until we will all be home. And believe me we will sure eat our folks out of house and home. I suppose you will receive this letter about Xmas so will Wish you a merry Xmas and a Happy New Year.

Wish Oceans of love for you all.

Your loving Brother and Son

Harold

The Caufield Family Waits

Every available man from the county signed up to go serve their county, leaving their families behind who prayed every day for their safe return. The Caufield family had four sons: three who joined the Army and one who joined the Navy. Mr. A. E. and Mrs. Helen Caufield were proud of their boys. They saw off two boys to Fort Lewis in Washington, and one was whisked away to a ship in the Atlantic. They said goodbye to their last boy, Royal Caufield, at Fort Harrison in Helena.

Royal Caufield was the first to be sent to France with the 163rd Infantry, which arrived on Christmas Day 1917. The family received a letter in February of 1918, but due to extreme censorship, it gave little more information than peace of mind. Another letter came in July. In September of 1918, the Caufield family received a letter from a Corporal Lawless. It told the story of how Royal gave his life in the Big Drive to push the Germans away from Paris and turn them back.

Corporal Lawless said he did not see Royal fall but did see his body afterwards. Some of the details did not match up, and because they did not receive an official wire from the War Department, the Caufield Family held out hope that the Corporal was wrong and that their boy was still alive. The War Department could not affirm the report and asked for patience as they worked towards confirmation. When the war ended, prisoners of war were released and returned to the American lines. Royal was listed as missing in action for several months until confirmation of his death was reached in January of 1919. He had indeed been killed in action in July 1918 at the Battle of Chateau Thierry. His body was eventually returned to Montana and buried in 1921. The other three sons returned home unscathed. In 1923, the new Great Falls VFW Post was christened the Royal A. Caufield Post.

From the Great Falls Daily Leader, November 5, 1918:

“There are but few parents in the United States who have four sons given to the service of their country at this time, as have Mr. and Mrs. A. E. Caufield of 908 Fourth avenue south of this city. Like Ex-President Theodore Roosevelt, they have four sons who left to fight for the flag. Mr. and Mrs. Caufield have lived in Great Falls for 28 years, coming here from Winnipeg, Canada, and during that time have been active in good citizenship in Great Falls.

“While others have given of gold and property, Mr. and Mrs. Caufield gave of their flesh and blood.”

Women Veterans of World War I

The following women entered the military from Cascade County, Montana. Most enlisted out of either the Columbus or the Deaconess Nursing Schools, with the exception of five nurses. Two women named above serve in the U.S. Navy as yeomen. Female yeomen served in administrative and clerical roles.

The women who served as nurses in WWI would not receive veteran status until after WWII.

Nurses from the Columbus Nursing School

Top row left to right: Mina Aasen, Harriet Aronson, Anna Curran, Virginia Flanagan, Lydia Fousek

Bottom row left to right: Mary Gregory, Wilhelmina Hume, Alma Hutton, Fleda McQuown, Marguerite Thompson

Nurses from the Deaconess Nursing School

Top row left to right: Efie Fowler, Grace Gibson, Cleo Peters, Elta Reed, Sarah Rollings

Deaconess Nurses Not Pictured:

Cora Craig, Emeline Gonczy, Amanda Larson, Bell Menzies, Ruff Clara

Nurses Not Pictured:

Ida Braughman, Sophia Jefferson, Elizabeth Shortreed

U.S. Navy Yeomen

Esther Hervin, Alice Parslow

World War I Roster for Cascade County

Two women in warm coats and hats pose beside a large sign reading “Soldiers & Sailors Register,” “Follow the Arrows,” “We need you - You need us.” [1999.069.0033]

The following link will take you to a compiled list of soldiers and sailors from Cascade County. The men listed lived in a Cascade County town at the time of their enlistment. Not everyone who went to war had an enlistment card, nor did they all fight in an American army - some chose to join an army overseas.

A note about Towns:

Some of the towns included in this list are currently not part of Cascade County. The towns of Geyser, Raynesford, Hughesville, and Spion Kop were separated from Cascade County into Judith Basin County in 1920.

A note about Comments:

Deserters were not always dishonorably discharged. Many people who deserted left immediately after the war was over, assuming their duty was done. This was common during the Civil War as well.

“Enemy Aliens” were often inducted into the military but then discharged due to their origin country. Some were citizens of neutral countries.

The original enlistment cards had a space designated to mark if the registering person was white or “colored.” “Colored” could mean African American, Native American, or Asian American. The armed forces were segregated at this time in history.

Many sources were consulted to create this list of Cascade County Soldiers. First was the History and Roster Cascade County Soldiers and Sailors 1919 book. These names were collected by the editors of the book and many of the men listed were submitted by their families. However, several of those listed did not live in Montana when they enlisted. Their families were here, but they were not.

Another source used was the WWI enlistment cards on Montana Memory Project website provided by the Montana Historical Society. A dedicated volunteer read through all of the enlisted cards, looking for those who had a Cascade County address at the time of enlistment, and added them to the list. Other names came from a few other sources, such as collections within our own archives, as well as the American Field Service website archives. We made every effort to list all we could find. If you see a name missing, please contact us. We want every Cascade County soldier to be recognized. 2,684 names have been collected.

Clicking this link will open a spreadsheet in a new window:

![Scrapbook page from Henry Hamilton Collection [1986.008.0017]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e9494ac1b86b3147a49c75e/1605288225728-PM558P3O77WP39AM3KBL/1986.8.17.jpg)

![Felt pillow cover from the Mildred Buntrock Estate, circa 1915 made to commemorate the 2nd Montana Infantry with text “U.S. Army on Mexican Border” [CCHS 132-96]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e9494ac1b86b3147a49c75e/1605221759564-EKKXHX49ER6RHUNMZ1FZ/cchs+132-96.jpg)

![Left: Helmet for the 91st Division (Pine Tree Division), originally belonged to Earl C. Wolff. [1991.146.1] Right: Helmet for the 41st Division, which included the 163rd Infantry Regiment Montana National Guard; helmet originally belonged to Albert …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e9494ac1b86b3147a49c75e/1605025208915-4NT9XNS5FABTIK45X1Z0/helmets.png)

![Two women in warm coats and hats pose beside a large sign reading “Soldiers & Sailors Register,” “Follow the Arrows,” “We need you - You need us.” [1999.069.0033]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5e9494ac1b86b3147a49c75e/1605307985135-AYWWS0CYWM5S4SAT28OG/1999.69.33.jpg)